By Meghan E. Gattignolo

Thanks to the Industrial Revolution, the 19th century was a time of extraordinary change. Industrialization changed the way everything was made. Manufactured objects and food products went from being made almost entirely inside homes or by a single person to being made in factories. Ingredients and substances were outsourced, creating an environment where a maker had less control over the overall quality of a product in favor of cheaper manufacturing.

Scientific advancements also made 19th century denizens excited for new things. This led to an environment where toxic chemicals could be found in just about anything, and the ignorance of the average consumer concerning the presence of these chemicals often led to their untimely death. Could you survive life in the 1800s?

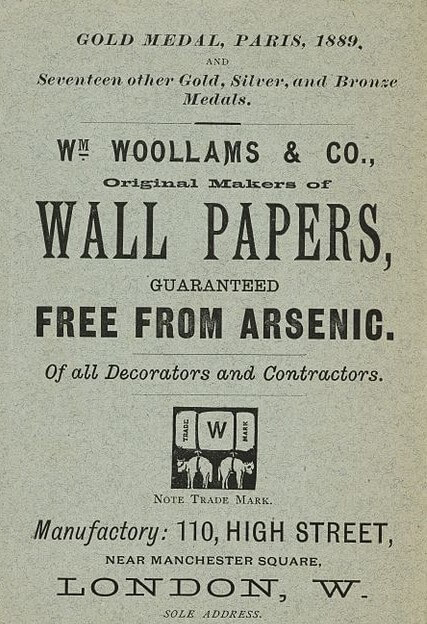

Advertisement for wallpaper free of arsenic, ca. 1890

Deadly DIY

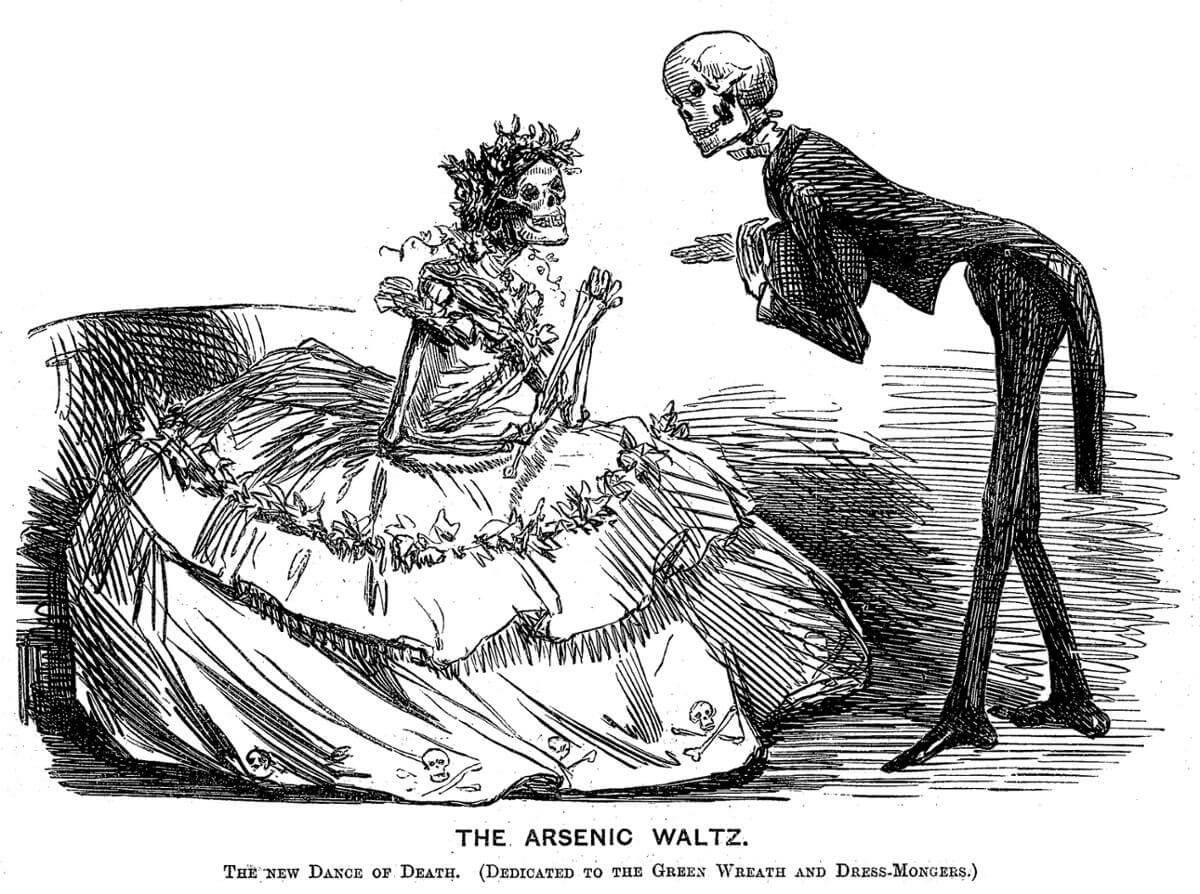

Today we take for granted that if we don’t like the color of our walls or we notice a hole that needs to be repaired, we just need to take a trip to the hardware store and fix it ourselves. Living in the 19th century, such a straightforward solution would not have been a great idea. Lead paint, arsenic wallpaper and asbestos in practically everything you owned was commonplace. If you wanted to redecorate your living room, simply stripping the walls could put the average person in contact with deadly poison. In the 19th century, the vibrancy of Scheele’s green made it a popular choice in decorating, particularly in wallpaper. The only problem: the pigment is made from arsenic. People living with this particular wallpaper would inhale the arsenic vapors the ink would give off when heated, or the ink chips when it flaked off with age.

Asbestos was also in just about everything. 19th century manufacturing made asbestos more readily available than the substance had ever been before in human history. Asbestos was favored for its resistance to heat and electricity, so as an insulator it was used in everything from steam engines to ovens. Asbestos is also fibrous, so it could be woven into textiles. Renovating a house or even moving the furniture around a room could prove dangerous to the average Victorian.

Bad Bread

People today take a lot of pride in making their own bread. In the 19th century, baking your own would be preferable – and safer. The least advantaged people of the era had to rely on unscrupulous bakers who had no problem sprinkling unhealthy and downright poisonous “special ingredients” into their dough to make their wares more profitable. Alum, chalk, plaster of Paris, clay and sawdust were just some of the ingredients found in 19th century bread, used either to bulk up the bread dough or whiten it. English doctor and social warrior John Snow noticed a correlation between bread consumption and illness. In 1857, he published an article in the Lancet medical journal addressing the problem of bad bread causing illness and malnutrition in England, especially in children he observed. Dr. Snow noticed that in regions where families were more likely to buy bread both in poor families and middle class, the instances of malnutrition were higher than in areas where families often made their own bread.

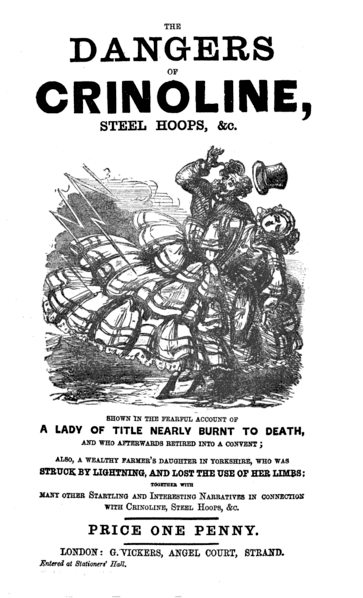

Title page with woodcut illustration to a short publication warning against the use of crinolines, 1858

Fatal Fashions

Social media users in the 21st century often look to influencers for the latest trends. Most of the time, the most popular clothing brands aren’t necessarily life-threatening. In the 19th century, however, fashion was often unhealthy, such as corsets that constricted organs, but some were also immediately dangerous. Crinoline – a fabric made of horsehair or cotton – was used densely in women’s petticoats and was highly flammable. Coupled with the dependency on candles and gaslighting to see at night, wearing those bulky hoop skirts to an evening party seems insanely risky today. All women, regardless of social class, lived everyday with the real danger of death by combustion. The arsenic-laced Scheele’s green was also used to dye fabric, so dresses in the trendy color were invariably toxic as well as flammable!

Want to hear more? Join the Customs House Museum & Cultural Center and Second & Commerce for a special Halloween History on the Rocks: A Listen and Learn Happy Hour on October 25th from 5:30 to 7pm Upstairs at Strawberry Alley Ale Works. Enjoy drink specials, trivia and plenty of interesting stories from history that will make your Halloween season complete. Come ready to learn and have fun!

Featured image: Etching of two skeletons dressed as lady and gentleman, 1862

Meghan E. Gattignolo is a freelance writer and longtime Clarksville, TN resident. She loves to obsess about historical subjects and annoy her family daily with unsolicited random facts. Meghan holds a History B.A. from Austin Peay State University and lives in town with her husband and two daughters.