By Meghan E. Gattignolo

Dunbar Cave State Park and the Friends of Dunbar Cave will be hosting a First Day Hike and Membership Drive on January 1, 2025. Indigeous peoples have used the cave and the land around the cave for tens of thousands of years.

Seeking Shelter and Safety

A cave is a natural place to hide from the elements. Though chilly, sometimes a cave can be warmer than freezing temperatures in winter, and it definitely helps cool off in the heat of summer. Shortly after Dunbar Cave became a Tennessee State Parks property in the 1970s, an archaeological dig performed inside the mouth revealed exciting clues to the cave’s past.

At the deepest level the dig reached, the State found projectile points that dated human presence at the cave at least as far back as 10,000 years ago. They also found the remains of campfires. Imagine a time when the chilly dark cave at your back and the fire in front of you was the coziest place you could be.

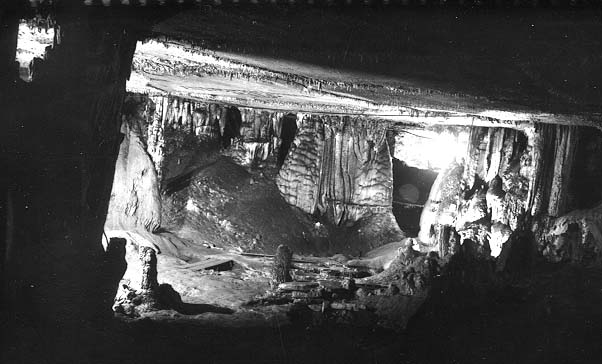

Dunbar Cave. Photo Courtesy of the Customs House Museum & Cultural Center Collections.

Telling Stories

From the turn of the 20th century until today, Dunbar Cave has seen a lot of traffic as a tourist cave. The scratched names of generations of Clarksville residents decorate the rough walls inside. Some areas of the cave were used for dances, parties, hiding places, and as a shelter in case of nuclear war.

Hundreds of years ago, members of the Mississippian culture were also telling stories inside the cave. Sandwiched among the century-old names, older drawings of celestial objects and supernatural figures were left behind. The purpose of the drawings can only be speculated on, but one likely theory is the Mississippians used the drawings to teach the next generation about their spiritual beliefs and to have respect for the Underworld.

Honoring Sacred Space

Even older than the drawings on the cave walls are the artifacts excavated from beneath the red clay and travertine in the same room. Travertine forms from the slow accumulation of mineral deposits from pooling water inside caves and is as hard as concrete. Under the travertine, experts found more indigenous artifacts.

The Mississippians thought of water as sacred within their belief system. Water can easily flow from one world to the next, and so watery areas are much like portals. The water in the cave would have been even more sacred because according to the belief system, caves are passageways to the Underworld. The presence of objects in an area where pools of water once stood signify that people likely were either leaving offerings to spirits of the Underworld in the hopes of positive outcomes, or they were simply showing reverence to a higher, unknowable being by leaving behind items important to them. Either way, the people who had access to the cave prior to European settlers moving in saw the cave as more than just a special place, but a sacred one.

Dunbar Cave. Courtesy of the Customs House Museum & Cultural Center Collections.

Leaving Messages

So much about how indigenous peoples in the past used the cave is lost to time, but one fact is made clear with the recent discovery of another find: the knowledge of Dunbar Cave as a sacred place has been passed down within indigenous communities.

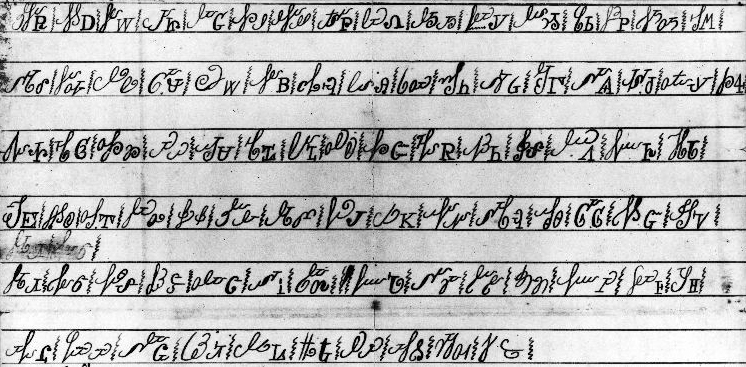

Soon after the passing of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, thousands of Cherokee were forced from their ancestral lands in North Carolina and Georgia, and some members of the Cherokee visited Dunbar Cave. We know this now because in 2019, Cherokee syllabary was identified inside the cave. Some of the writing is dated, so we know that some of it was left behind in the mid-19th century. It’s not common knowledge what the syllabary says, but most likely they’re names left to remind and inform future Cherokee visitors to the cave.

Sequoyah’s original syllabary characters for the Cherokee language, showing both the abandoned script forms and the lithographic forms. circa 1820. Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain.

Staying in Touch with the Past

Today, members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee still come to Dunbar Cave at least once a year. Members come on their own to explore a place their ancestors sought out for one purpose or another, or they come in groups.

Since 1984, young adults with Cherokee heritage take part in a bike ride through areas touched by the Trail of Tears. As of 2009, the Remember the Removal Bike Ride has become an annual event that allows young Cherokee to experience their history by seeing the places where their ancestors once tread. Dunbar Cave State Park has become a part of this important event since the discovery of the Mississippian cave art. Participants in the Bike Ride get a special cave tour tailored to the theme of their journey.

Dunbar Cave is a complex place that enjoys layers of history and cultural context. Today, it can be easy to forget how long the cave and surrounding area has been important to people. Next time you visit the cave and the park, reflect on how ancient Dunbar Cave truly is and how lucky we are in Clarksville to have such a deep cultural touchstone.

First Day Hike & Friends of Dunbar Cave Membership Drive:

To sign up for the First Day Hike, visit Dunbar Cave State Park here.

Learn more about the cave! If you become a Friends of Dunbar Cave member, you receive one free annual cave tour per individual/student membership. Family memberships receive 4 free cave tours. Friends of Dunbar Cave members also have the opportunity to become docents and help with cave tours. Speak to a Friends of Dunbar Cave representative on January 1, 2025, to learn more.

Resources:

Featured Image: Dunbar Cave. Acrylic. Courtesy of Peg Harvill, from the Customs House Museum & Cultural Center Collection.

https://remembertheremoval.cherokee.org/about.html

Meghan E. Gattignolo is a freelance writer and longtime Clarksville, TN resident. She loves to obsess about historical subjects and annoy her family daily with unsolicited random facts. Meghan holds a History B.A. from Austin Peay State University and lives in town with her husband and two children.